Edition 9 — Kim Lim

Weaving women back into the history of art with Jo McLaughlin's profile on the stellar career of Singaporean-British sculptor and printmaker Kim Lim.

I’d like to start off this weeks post with a little anecdote. For a number of years, I had the pleasure of curating and installing The Portia Geach Memorial Award, when I worked at S.H. Ervin Gallery. I wrote about it once.

Portia Geach was a prolific artist of her time. Despite exhibiting in London, New York, and Paris in the late nineteenth century, Portia was left out of the history books. The reason? She was a woman, duh. *Men, for the most part, were in charge of writing art history. All of this is to say that after Portia’s death, her sister Kate, created Portia’s legacy: The Portia Geach Memorial Award.

The prize is an annual, celebrated feature of the exhibition calendar. However, each year, the same male journalist responded to our press release. ‘But why is this open only to women? Isn’t that sexist?’ Every year we gave him the same response—that opportunities for female artists to be recognised in male-dominated spaces are significantly less for women. ‘Therefore’, we said, year after year after year, ‘prizes such as this were established in an effort to equal the scales.’

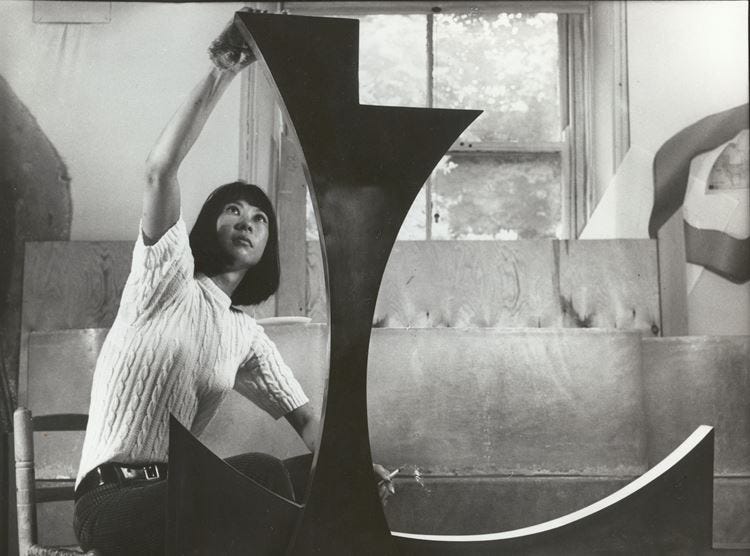

Kim Lim, pictured above, is another female artist who has been stitched back into the rich tapestry of our collective art history. Although the two have different stories, Kim faced similar struggles to Portia. Kim travelled from her home country for her art. Kim exhibited internationally, too. This week we are featuring words by arts writer Jo McLaughlin, who paints the picture of Kim’s work and life. Times are changing for the better, and institutions have recognised Kim’s incredible legacy and are working to reintegrate her story into the canon of art history. We hope that after reading this post, you remember her name, too.

Jo McLaughlin is an art historian, curator, writer and arts for all champion. Jo writes and presents on all topics art historical, plus hosts her own podcast, Jo's Art History. You can find her here, here, and here.

*Not all men.

Lead image: Kim Lim in her London studio, 1966. Image rights Turnbull Studio, via Ocula

Kim Lim.

Sculpture and printmaker. The incredible life and work of a prolific artist.

Words by Jo McLaughlin.

‘Being female and foreign was never a problem as a student, later I realised there was a difference but what was important, in the end, was what I did and not where I came from.‘

Kim Lim

Kim Lim is not the first female artist to slip through the cracks within the canon of art history, and she certainly is not the last. Kim herself, although an incredibly talented and prolific maker in her lifetime, fell fate to being side-lined by historians as the wife of British artist William Turnbull.

Thankfully, however, this is changing. More than 20 years after her death, Kim Lim’s work is slowly emerging to take its rightful place in the spotlight alongside her contemporaries thanks to a select few who fiercely fought for her recognition.

Born and raised in Singapore, a determined 17-year-old Kim travelled alone to London to study art at the renowned St Martins Art School in 1953. There she fell under the tutelage of Sir Anthony Caro in 1954. Like most who studied under Caro at this time, Kim was encouraged to explore a vast range of materials within her practice, before transferring to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1956 to concentrate on her love of carving and printmaking.

Through her career in the UK, Kim refused to be ‘othered’ as a foreign artist living and working in London. This no doubt inspired her famous refusal to exhibit in ‘The Other Story’ at London Hayward in 1989. The exhibition highlighted works of African and Asian artists working in post-war Britain. Kim’s resistance to being pigeon-holed in such a way speaks volumes for her strength of character and self-belief.

Kim met and married fellow artist William Turnbull in 1960. The two began building their life together in London, where Kim settled permanently. Her first solo exhibition took place in London in 1966, and she began exhibiting her work extensively throughout the UK, Singapore and abroad. During her life, Kim’s dedication to exhibiting was extensive, a list of which can be found on her website. A lack of work and willingness to exhibit is clearly not the reason behind her marginalisation.

Kim’s canon can be divided into two periods. From the 1950s – 1970s, she embarked on a sculptural exploration of bronze, brass, wood and fibreglass. During this period she also had a rich printmaking experimentation practice. Kim’s prints evolved around linear exploration. Her Bridge series is an excellent example of the power and simplicity in her work. After her mid-career retrospective at the Roundhouse London in 1979 Kim’s focus turned to carving in stone and marble, which became the crux of her work until she passed away in 1997.

The beauty and simplicity of form which Kim moulded through her life’s work is unceasing. Her pieces draw you in and allow you to stay for as long as you need before moving with a feeling of peace and enrichment.

Kim’s stonework in particular is something to marvel at. Its tactical nature is undeniable. Her love of Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși and passion for ‘truth to materials’ is evident in her simplified organic carvings. This passion is clearly demonstrated in her works Wind-Stone and Column P, pictured below. Their smooth and minimalistic surface markings show in particular how easy it is to underestimate the talent in making something so beautiful, appear so modest.

Kim never worked with assistants, preferring everything to be by her hand, much the same attitude as her husband. Both had separate studio spaces within the family home. Their two sons, Alex and Jonny – who now run both estates – remember their mother always in the garden carving.

Throughout her lifetime Kim’s presence on the British art scene was wide and impactful, standing out as a female sculptor in a male-dominated space. Yet she all but disappeared from the narrative once she passed away. Knowing what we know, it would be naive not to consider two factors that made it all too easy for Kim to slip into the margins: being female, and foreign.

Kim took great care of the works she made. Her estate now holds incredibly rare works from the 1950s and 60s in near perfect condition. Storage and collection care can sometimes be at the bottom of an artist’s agenda, especially for those who prefer to look forward into their making rather than reflecting on what’s already been done.

Sadly, Kim suffered an early death at 61. Now, some 20 years after her death, Kim Lim’s life and work is receiving its rightful recognition. Her sudden recognition is an accumulation of elements. Not least the dedication of her sons who run the estate but in a select number of institutions and researchers who’ve been wise enough to allow their inquisitive minds to dig deeper to uncover something which the art world was in danger of losing sight of.

2020 saw Tate Britain dedicate an artist Spotlight room to Kim Lim’s early sculpture and prints following on from a selling exhibition at Sotheby’s S|2 gallery in 2018. Each institute played its part in encouraging art lovers and collectors alike to re-evaluate Kim’s importance and place within art history.

The reconstruction of art historical narratives is long but exciting. If the art world had almost forgotten Kim, just imagine the other talent’s waiting in the wings for their long over-due moment in the sun.

Image credits from top to bottom:

Queen, marble, 1984 via the189.com

Padma (left) marble, 1984 and Slate relief (right), slate, 1995 via FTimes

Wind-Stone, stone, 1992 via Sotheby’s

Column P, stone, 1984 via Sotheby’s

Bridge II, lithograph, 1960 via Tate

Split Red, lithograph, 1960 via ArtNet

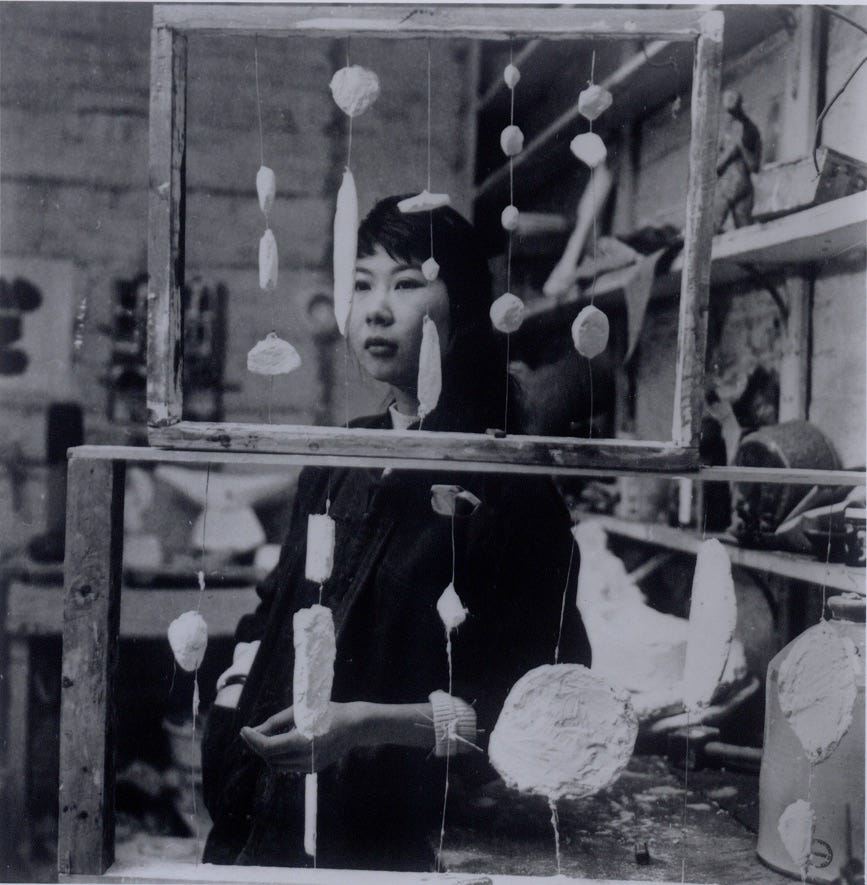

Kim Lim in her studio, 1959 via ArtNet

Request a comp subscription · Connect on socials · Share your feedback · Share with a friend · Write for Sprout