Flash Minky: The artists who taught us to combine beauty with sustainability

Flash Minky is a sustainable textile brand creating affordable artworks by Western Australian artists

It has been an unusual week in London weather. The days are chilly but sunny, and the sky has (for the most part) been a glorious shade of blue. Although I relished London’s sunny winter days this week, I found myself longing for blue skies back home. The Australian sky is so expansive it seems to roll on and on forever.

To cure my homesickness, this week we are diving into the archives to remind us of the joy that can be found in Flash Minky blankets. I chatted with Emilia Galatis, Founder of Flash Minky in May 2021. We spoke about how Flash Minky artists feel about the brand and what opportunities it has carved out. Emilia speaks vibrantly and passionately about indigenous art, its reception, and empowering changes that are emerging in the industry.

Subscribers can explore here to watch the full conversation between Emilia and myself. If you haven’t subscribed yet, treat yourself to paid subscription here.

I found our conversation inspiring and insightful, I hope you do, too. ■

“English is incapable of describing our relationship to the land of our ancestors. We decided to … [describe] it in a way we hoped non-Aboriginal people would understand; through pictures. If they wouldn’t listen to our words, they might try and understanding our paintings.”

- Galarrwuy Yunupingu, 1989

Having worked with indigenous artists and remote communities in Western Australia for well over a decade, Emilia Galatis wants to shift the way mainstream audiences view and engage with indigenous art. Enter: Flash Minky, a brand that creates unique soft furnishings in collaboration with blue-chip indigenous artists.

Flash Minky evolved through countless conversations and cups of tea with artists. The brand came into being as a solution for artists to earn passive income from a product that was environmentally sustainable. “The artists that I work with have obviously been looking after their country areas for over 60,000 years and so they are not a culture of wasters. They’ve had a long genesis of caring for places,” Emilia explains.

Artists submit an image of their work that is then licensed for 100 prints, or, 100 blankets. The image is woven into a blanket using recycled cotton. It’s kind of like buying an artist’s print as opposed to a painting, but for textiles. They include Minnie Lumai, Ben Ward, Betty Bundamurra, Louise Malarvie, John Price Siddon, Ngarralia Tommy May, Sonia Kurarra, and Tywrone Waigana. To be clear, paintings by these artists are generally not affordable for the average Joe or Jane. In creating these products, each artist is ultimately able to offer the market a product that is both affordable and accessible.

Much like the works themselves, the concept of a blanket is steeped with meaning and representation. “Blankets are a form of currency in remote communities,” Emilia explains. In all their brightly coloured glory they have cultural significance and power in expressing individuality.

Blankets are gifted at funerals, used when travelling, and are treasured for life. For Flash Minky artists, it means they can engage with their work in new ways by wearing it, and keeping it. Conversely, most paintings they make are replaced by a cheque and sent off into the world.

Flash Minky celebrates the diversity of place, region, culture, individuals, and artistic expression. Having worked within the sector for a long time, Emilia has observed the hesitation people often encounter when engaging with indigenous art.

She sees Flash Minky as an opportunity to “mobilise unfamiliar narratives and get this beautiful art to people’s houses”. Blankets don’t carry the baggage of interpretation or knowledge; it’s less daunting to buy a blanket than it is a painting.

Indigenous artists have, from the very beginning, been making art. The early incentive for selling Arnhem Land bark paintings and acrylic Western Desert dot paintings was to earn money in telling non-indigenous people about each artist's land rights and cultural heritage. A visual representation of history and ownership.

Artist Minnie Lumai tells stories through her work. “My paintings are about the stories of my country and culture - the way the land is from the dreaming and where we travel to hunt and fish.” In Minnie’s piece, Bubble Bubble (pictured above) the playful shapes she creates truly are reminiscent of bubbles; floating together in a fluid motion. Ochre colours and shades of white evoke a distant memory of water lapping at the edge of land.

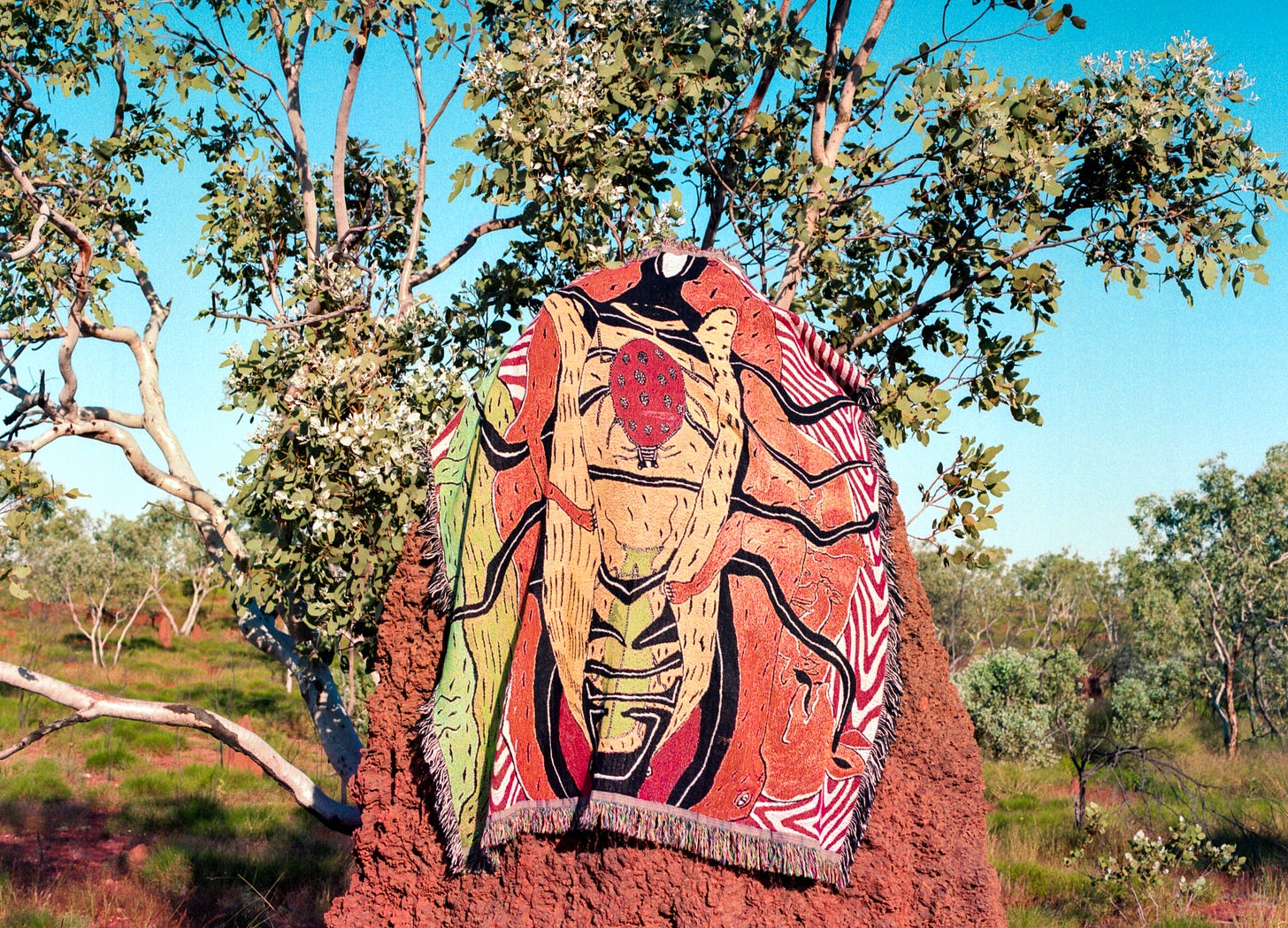

Not all stories are for sharing, though. Some, like the land, are sacred. Telling a story that is not your ancestral rite to share is considered risky and dangerous. Ngarralja Tommy May tells ‘easy stories’ that can be shared, not cultural secrets. Most of his later works are Dreamtime narratives enmeshed with his lived experiences and connections to place. The Billabong Blanket (pictured below) is an example of this.

Emilia describes the artists she has worked with as “Very savvy and entrepreneurial as to what their skills are…[they] see art-making and creativity as intrinsic to their existence but also this incredible culture that we’ve really only scratched the surface of understanding”.

On the mainstream representation of indigenous art, she says “I think the way it’s been marketed and promoted over the last 40 years has been really poor, and it hasn’t done the diversity of the country any good, but we are in really exciting times”. She goes on to describe a new wave of younger and older artists who recognise their power in expressing individuality in their artwork as a matter of urgency, not reliant on the market.

Brands like Flash Minky help indigenous artists in these endeavours by championing their work whilst simultaneously ensuring they are properly financially rewarded. It is this—aside from the aesthetics and creative freedom of the products—that is most striking about the brand.

100% net profits from sales go directly to the artist, which is significantly more than they are used to receiving for sales of their work. Although it is not necessarily a sustainable business model in the long term, it represents a shift within the indigenous art sector.

What is next for Flash Minky? Aside from evolving with how artists would like to grow, Emilia stresses the importance of art as an agent of change toward greater cultural awareness and knowledge. Speaking on the difference between regions in the Kimberley, she says she wants people to understand the diversity of geographical regions and creative communities within the area.

Follow Flash Minky on Instagram here and check out their online store here.

Images from top to bottom:

John Price Siddon, Panic! John Price Siddon, The Great Escape Betty Bundamurra, Kira Kiro Spirits Minnie Lumai, Bubble Bubble Ngarralja Tommy May, The Billabong Blanket Louise Malarvie, Milk Water Ben Ward, Goorloordoordoog (Dunham River Country)

All images courtesy the artist and Flash Minky

Carve out time to make your goals a reality in 2022.

Sell Your Writing course modules open today, and I cannot wait to start learning with the latest cohort! The first workshop takes place on 26 January 2022, which means there is still time to join!

Make time to write, hear feedback on your work and be inspired by guests to keep you motivated on your writing journey.

Sell Your Writing is priced as affordably as possible at only £15 per week. Payment plans are available so you can pay as you learn 💸

Read the full curriculum and enrol here.

Hear what past participants have said:

"I came into this course a little jaded by online workshops, post-pandemic, but was positively surprised by the many practical exercises...I had the feeling Claire enjoyed teaching the course and was genuinely interested and supportive of our writing while still providing valuable feedback..."

Thanks for reading!

Connect on socials 🔸 Write for us 🔸 Vote for features 🔸 Contact Sprout

So great to revisit Flash Minky. Thankyou for the Instagram link!